Understanding Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder

Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder, or OCD, was categorized as an anxiety disorder until 2013 when the DSM-5 was published and categorized OCD as a separate and distinct diagnosis.

About 1 in 100 adults and about 1 in 200 children in the U.S. have OCD. While you can be diagnosed with OCD at any age, many people start to exhibit symptoms between the ages of 8 and 12 or in early adulthood.

OCD is a chronic illness. By engaging in evidence-based mental health treatment, individuals with OCD can control the symptoms and manage the associated disability. A combination of evidence-based therapy and medications is effective for about 70 percent of individuals.

Like many mental illnesses, symptoms of OCD may wax and wane over time. Life transitions, significant losses, or physical illnesses can exacerbate OCD symptoms, as can the use of illicit drugs and even some over-the-counter medications and caffeine.

One of the goals of psychotherapy for OCD is to help patients learn skills that they can use to prevent the escalation of OCD symptoms and to learn how to ask for help and support when needed. Treatment for OCD should involve family members, educators, and other individuals in the patient’s support system to ensure that everyone is encouraging healthy thoughts and behaviors instead of unintentionally reinforcing the cycle of obsessions and compulsions through reassurance.

What is Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder?

To be diagnosed with OCD, you must have obsessions. Obsessions are ruminative and intrusive thoughts centered on a singular idea or concern. These thoughts often cause fear or worry and they dominate someone’s thinking for at least one hour each day (though a majority of patients with OCD report that they experience obsessive thinking for most of the day). Some common themes for obsessions are:

- concerns about your physical appearance

- fear that you will hurt someone

- worry that you will become sick or “contaminated”

- the belief that you or someone you love is in danger

- concerns about being perfect

Some people with OCD also have compulsions, though compulsive behaviors are not required for an OCD diagnosis. Compulsions are behaviors that someone performs or completes in an attempt to “undo” the obsessive thoughts they are experiencing. Sometimes the link between the compulsion and the obsession is clear, like someone who washes their hands repeatedly to fight germs or contamination. Other compulsive behaviors—like repeatedly touching objects—are not obviously connected to the content of a person’s obsessions.

Compulsions are behaviors that someone performs or completes in an attempt to “undo” the obsessive thoughts they are experiencing.

For many people with untreated OCD, these symptoms cause fear, emotional pain, and disability. However, some people find their thoughts and behaviors intrusive and time-consuming, but not necessarily worrisome or frightening.

Diagnosing OCD, “The Great Imitator”

In psychiatry, OCD is sometimes referred to as “the great imitator” because the behaviors of someone with OCD can look like symptoms of many other disorders. Psychiatric evaluation by a mental health professional is a crucial first step to ensure patients with OCD receive an accurate diagnosis and are matched with an evidence-based treatment plan. Effective treatment for psychosis likely will not be an effective treatment for OCD. A good match from the start helps prevent treatment burnout, wasted resources, hospitalizations, and other poor outcomes.

OCD Can Look Like…

OCD and Psychosis

Compulsive behaviors can sometimes appear disorganized or psychotic –for example repeatedly touching objects, ordering and reordering objects, or washing your hands over and over. If a patient does not disclose or is not able to verbalize the obsessive thoughts they are experiencing that are driving the compulsive behaviors, without a thorough psychological assessment, the patient could be misdiagnosed with a thought disorder. Treatment for thought disorders is very different from evidence-based treatment for OCD.

OCD and Tourette Syndrome

Compulsive behaviors—like repeatedly touching your nose or blinking—sometimes look like Tourette Syndrome. The behaviors of someone with Tourette Syndrome or a tic disorder are not driven by obsessive thoughts. Treatment for Tourette Syndrome also would be very different from treatment for OCD.

OCD and Depression and Anxiety

In addition, because people with untreated OCD are frequently in continual distress, they may develop comorbid depression and/or anxiety. As a result, without a thorough diagnostic assessment, some individuals with OCD may initially receive treatment for a primary diagnosis of depression or anxiety based on their presenting symptoms.

OCD and OCPD

Often when people colloquially refer to behavior or approach as “OCD”—for example, “My boss is SO OCD about filing!”—they are really referring to Obsessive-Compulsive Personality Disorder or OCPD. Someone with OCPD may have rigid behaviors in certain situations or may prefer to do things a certain way.

Someone with OCPD may have rigid behaviors in certain situations or may prefer to do things a certain way.

People with OCPD do not have obsessional thinking for hours a day, which is disabling. And people with OCPD do not have compulsions. They have a desire for things to be done in a certain order; they like routine and organization. Their behavior stems from a personality characteristic and is not compulsive behavior driven by obsessive thinking.

Children and adolescents cannot be diagnosed with OCPD or any other personality disorder.

OCD and Co-Occurring Disorders

OCD and Depression

OCD often co-occurs with mood disorders like major depressive disorder. If you spend hours a day ruminating on a fear that you will get sick or someone you love will die, you are more likely to develop symptoms of depression. In addition to feeling sad or having a low mood, someone struggling with obsessive thoughts may also isolate, withdraw from relationships, and stop engaging in activities they once enjoyed. These are also common symptoms of depression.

OCD and Anxiety

Though no longer classified as an anxiety disorder, OCD is still strongly linked with anxiety. Many adults and teens with OCD have a fear of what will happen in the future and a strong desire to try to control the environment around them. These are common features of anxiety. Further, if untreated, specific obsessions associated with an OCD disorder can contribute to the development of generalized anxiety disorder which can exacerbate unhealthy behaviors like isolation or substance use.

OCD and Substance Use

A high co-morbidity exists between OCD and substance use. Many patients report that they use to get relief from obsessive thinking. That relief is temporary, however, and, without addressing the obsessive thinking, both the OCD and the substance use can become disabling.

Someone with symptoms that could be connected to many disorders should have a thorough psychiatric assessment to determine which symptoms are part of a constellation of symptoms caused by OCD and which symptoms are in fact caused by a separate co-occurring disorder. Sometimes, the related mood and anxiety symptoms resolve with effective treatment of OCD. In other circumstances, such co-occurring disorders require interventions in addition to those used to treat OCD.

Diagnostic Testing for OCD

Because symptoms of OCD look like symptoms of many other disorders and can co-occur with mood, anxiety, and substance use disorders, a thorough psychiatric assessment is paramount to an accurate diagnosis and effective treatment plan. Many people with OCD are initially misdiagnosed.

OCD can be diagnosed in children, adolescents, and adults. It may be difficult for children or adolescents to explain their compulsive behaviors. To a parent or teacher, that behavior may look oppositional or disorganized. So a child that is seen as “acting out” or “being defiant” may in fact be struggling with burgeoning compulsive behaviors in response to obsessive thoughts.

Families who are worried about their child should arrange for a psychiatric assessment. There are psychological tests that can be helpful in distinguishing between diagnoses.

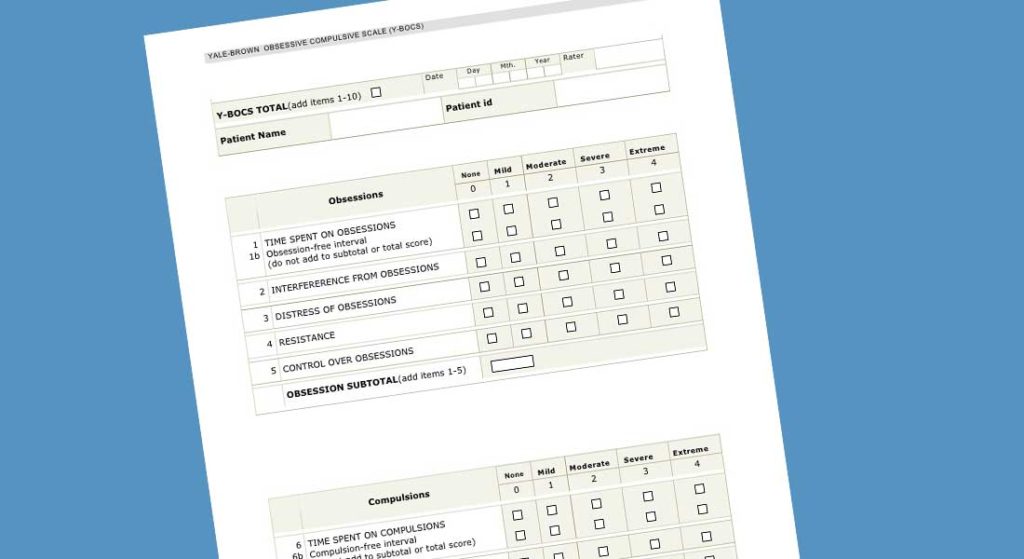

Parents or families who are worried that their child or adolescent may be exhibiting symptoms of OCD should arrange for their child to have a psychiatric assessment. Treatment will work best when it is specialized to address the specific diagnosis and symptoms of the patient. There are normed psychometric instruments—psychological tests—that can be helpful in distinguishing between diagnoses. The Yale-Brown Obsessive-Compulsive Scale, or Y-BOCS, is particularly useful in diagnosing OCD.

Evidence-based Treatment for OCD

There are two evidence-based psychotherapeutic treatments for OCD: cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) and exposure and response prevention therapy (ERP).

CBT for OCD

Cognitive behavioral therapy helps patients develop skills to interrupt their obsessional thoughts. They learn to see themselves as separate and independent from their thoughts. They learn that thoughts are not facts. And they learn that they can be in control of how they respond to those thoughts.

Some CBT skills focus on patterns of thinking—learning to replace an unwanted obsessional thought with a substitute or to reframe a thought through a different lens or perspective. Other CBT skills help clients learn behaviors to confront obsessional thoughts. When they have the impulse to wash their hands, is there another action they can take instead to confront the thought instead of confirming it?

ERP for OCD

In exposure with response prevention (ERP) therapy, a mental health professional supports a patient while they experience an obsessional thought or fear in real-time and prevents them from engaging in compulsive behavior. For example, if a patient is obsessed with a fear of contamination and repeatedly washes their hands, they would be asked to enter a dirty environment and touch garbage or an unclean floor. The therapist would take the same action with them. And then the therapist would provide support and coaching to help the patient manage their anxiety and not wash their hands. With repeated exposures, a patient builds a body of evidence—“proof”—that, although unpleasant, having dirty hands doesn’t kill or disable you. Over time the patient can refute the obsession and it loses meaning and power. The patient also establishes a history that can be used when future obsessions emerge.

In ERP therapy, a mental health professional supports a patient while they experience an obsessional thought or fear in real-time and prevents them from engaging in compulsive behavior.

Previously, therapists approached ERP for OCD using an “anxiety hierarchy,” where patients would start with exposure to something slightly distressing and then work their way up to the worst possible scenario they can imagine. More recent research suggests that an “anxiety lottery” is the better approach. In an anxiety lottery, the patient writes down 10 distressing situations of various magnitudes on 10 slips of paper, along with a couple of “passes,” and then chooses one. In this approach, the patient is not able to predict the next exposure, and this seems to improve the obsessional thinking and compulsions more quickly than working through an anxiety hierarchy linearly.

Medications for OCD

Medications are important for OCD. There are only two medications that have been FDA approved to treat obsessive-compulsive disorder. Psychiatrists do prescribe other medications for OCD, typically SSRIs and tricyclic antidepressants. Treatment of OCD usually requires a higher dosage of these medications than what would be prescribed for a patient with depression or other anxiety disorders.

Family Therapy for OCD

OCD often impacts the family in a way other illnesses do not. The natural inclination for parents or other caregivers is to reassure. “Everyone is ok. No one is going to get hurt or die.” Unfortunately, research shows that reassurance is actually counterproductive and can make symptoms worse. The reassurance, though well-intentioned, can reinforce the obsessional thought in the mind of the person experiencing OCD.

Through family therapy, parents and siblings learn how to support the patient as they use skills to confront obsessional thoughts instead of playing into the cycle of reassurance.

Family therapy is therefore an important part of treatment for OCD. Through family therapy, parents and siblings learn how to support the patient as they use skills to confront obsessional thoughts instead of playing into the cycle of reassurance.

OCD and Schools

A lot of work the individual patient is doing in treatment through CBT and ERP can be undone if the people in that patient’s support system are not educated about how to appropriately support someone with OCD.

Schools and educators need to know if a student has OCD, particularly if the student’s obsessional thinking is about perfection or doing things in a specific order. Those students need to be in classes that don’t emphasize perfection as the goal or require adherence to a rigid and precise approach to learning for achievement. For example, if a student’s obsessive thinking focuses on perfection, and the compulsive behavior is studying all of the time, the curriculum would need to be adjusted for that student to prevent them from spiraling out of control.

The natural reaction of many teachers, like parents, would be to reassure the student who was struggling with obsessive thinking. Educators who receive training about supporting a student with OCD can be an important part of helping a student achieve success in school and long-term health outcomes.

Other Treatments for OCD

New research is exploring the potential of other treatments for OCD. Some preliminary evidence suggests that anti-fungal medications may be helpful for some people, but not enough evidence exists to date to indicate that anti-fungal medications should be the first-line treatment. This line of research is related to the possibility that the etiology of some OCD diagnoses could be related to infections, particularly infections like rheumatic fever during childhood. Research is ongoing in this area.

OCD and Social Media

Research has not yet specifically linked social media with OCD. However, many studies have reported evidence that unhealthy social media use exacerbates many mental illnesses like anxiety and depression. Individuals with OCD whose symptoms are related to “checking” may be particularly impacted by social media. Social media platforms are based on encouraging users to frequently “check” the status of their friends, the world, and others’ reactions to photos or content they’ve posted. Building skills for healthy social media use can be a valuable part of OCD treatment, particularly for adolescents or teens with OCD.

Individuals with OCD whose symptoms are related to “checking” may be particularly impacted by social media.

Finding the Best Treatment for OCD

After receiving a diagnosis of OCD from psychological testing or a psychiatric assessment, patients and families should look for specialized mental health treatment for OCD. Look for a licensed therapist with specific training and experience in CBT and ERP for OCD. Similarly, connect with a psychiatrist with experience dosing medications for adults or adolescents with OCD.